Comparing Pre-trained Language Models with Semantic Parsing

Published:

In my last post, I showed how adding ELMo features to a seq2seq model improved performance on semantic parsing tasks. Recently, I have been experimenting with adding OpenAI GPT and BERT to the model in order to compare their performance against ELMo’s. All the data, configuration files, and scripts needed to reproduce my experiments have been pushed to the GitHub repository. I’m excited to share my results!

TL;DR: I was able to achieve significant gains in performance on several semantic parsing datasets above a vanilla seq2seq baseline by utilizing a “scalar mix” of pre-trained features from ELMo, OpenAI GPT, and BERT. OpenAI and BERT produce the strongest results, likely due to being trained either with more data or with data with more long-term dependencies. I believe this work is the first application of pre-trained language models to semantic parsing and the first application of the recent ELMo, OpenAI GPT, and BERT language models to any language generation task.

Improved Results on Baseline and with ELMo

| Model | ATIS | GEO | JOBS |

|---|---|---|---|

| S2S + attention (old / new) | 75.2 / 79.9 | 62.5 / 68.9 | 58.6 / 71.4 |

| S2S + attention + ELMo (old / new) | 79.0 / 83.3 | 71.1 / 75.7 | 74.3 / 77.9 |

I was able to significantly improve all the results reported in my last post, providing a stronger baseline against which to compare OpenAI GPT and BERT. I was able to achieve this improvement primarily through these three changes to my original code:

- Early stopping is now performed with sequence accuracy on the validation set (previously validation loss). This allows the selection of better models by directly measuring the type of performance we’re actually looking for.

- Training for a maximum of more epochs and with greater patience for early stopping.

- Keep separate vocabularies (and tokenizers) for the source- and target-side languages. This probably had some effect on performance of the baseline and ELMo models, but is more important for direct comparison to OpenAI GPT and BERT, which use different tokenization methods.

The rest of this post includes a semi-formal write up of my all methods and results.

Methods

Sequence-to-Sequence with Attention

My baseline is a sequence-to-sequence LSTM network with an attention mechanism.1 This architecture has already been successfully used in semantic parsing.2 3 All experiments utilize the same sequence-to-sequence architecture: a bidirectional encoder with 200-dimensional hidden units and 100-dimensional embeddings, a bilinear attention mechanism, 100-dimensional embeddings for the decoder, and a beam search of 5 for decoding.

Pre-trained Representations

For all other models, exactly the same sequence-to-sequence model is used as in the baseline except for the input layer for the encoder. Pre-trained representations are only included for encoding the source-side English questions and not the target-side logical queries; the decoder’s embedding layer is still randomly initialized and trained normally. For the encoder, the 100-dimensional embedding layer is initialized with GloVe embeddings,4 and the input to the LSTM is the concatenation of this 100-dimensional embedding with the representation of the sequence provided by the pre-trained language model used. The GloVe embeddings are allowed to be tuned during training; the pre-trained language models are frozen and instead use a learned “scalar mix” of activations from the pre-trained language model. Thus, the input to the LSTM encoder for the $k$th token $t_k$ in the sequence is

\[\mathbf{e}_k = [\mathbf{r}_k; \mathbf{g}_k]\]where $\mathbf{g}_k$ is the 100-dimensional GloVe representation of $t_k$ and $\mathbf{r}_k$ is the pre-trained representation of $t_k$:

\[\mathbf{r}_k = \gamma \sum_{j=0}^L \mathbf{s}_j \mathbf{h}_{k,j}\]where $\mathbf{h}_{k,j}$ is the activation associated with the $k$th token in the $j$th layer of the pre-trained model, $\gamma$ is a learned scalar parameter, and $\mathbf{s} = \text{softmax}(\mathbf{w})$, where $\mathbf{w}$ is an $L$-dimensional learned weight.

This “scalar mix” approach is essentially equivalent to the one used by ELMo,5 whereas ULMFiT,6 OpenAI GPT,7 and BERT8 all utilize a “fine-tuning” approach, in which the entire language model is instead tuned to the downstream task. There are several motivations for using the scalar mix approach in this comparison.

First, it precludes the necessity of determining the best approach to fine-tuning. There is no clear consensus on the best method to fine-tune models in order to avoid the problem of catastrophic forgetting, in which the knowledge contained within the pre-trained language model is destroyed as the model adjusts its weights to the target task. ULMFiT uses a combination of discriminative learning rates (different rates for each layer) and layer freezing/unfreezing, OpenAI GPT uses an auxiliary language modeling objective, and BERT ostensibly does not use any technique to avoid catastrophic forgetting. By instead freezing the models and learning how to best utilize the information already contained within them, it is possible to more directly compare their effectiveness.

Moreover, using a scalar mix precludes devising special methods that would be needed to fine-tune pre-trained language models for language generation tasks. Ramachandran et al. (2016) demonstrate one such approach on a sequence-to-sequence model for machine translation.9 They utilize residual connections between the pre-trained layers and the randomly initialized RNN encoder-decoder layers, jointly train the seq2seq objective with language model objectives for both the source and target sides, and initialize the softmax layer on the target side with the weights learned with the target-side language model. Implementing such an approach would be substantially more difficult, whereas using a scalar mix allows one to essentially “plug in” pre-trained models into existing sequence-to-sequence implementations. Further, it is unclear as to whether or not a language model for the target-side logical denotations would be necessary, or, even if so, the choice of data on which one might be trained.

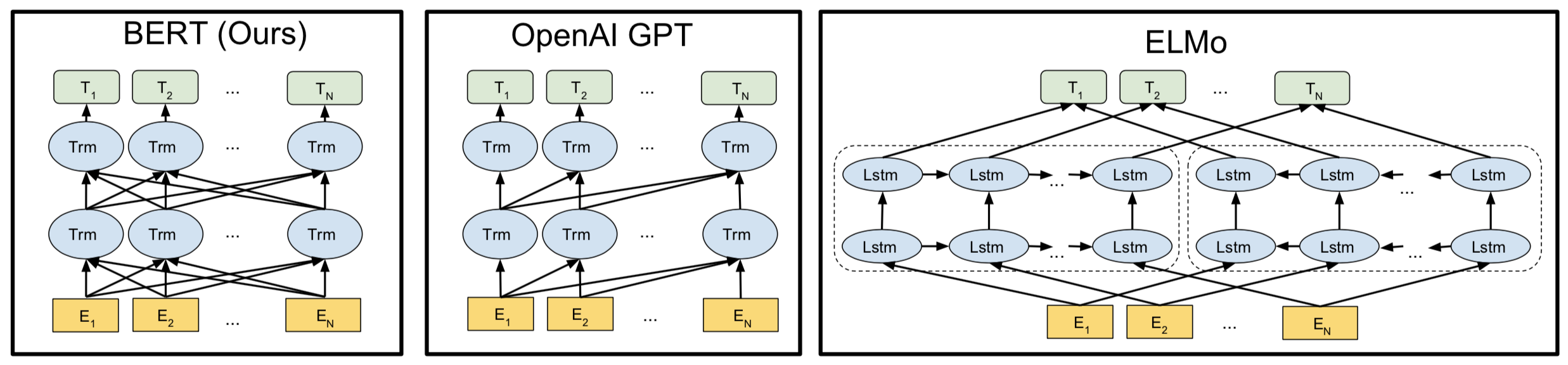

The rest of this section details how $\mathbf{h}_{k,j}$ is calculated by each of the pre-trained language models used in these experiments and provides some relevant background information for each. The following image provides a visual comparison of the three approaches (taken from the BERT paper).

ELMo

ELMo utilizes a “biLM” architecture which consists of independently trained forward and backward LSTM language models (with the exception of jointly trained embedding and softmax layers). These representations are concatenated together to produce the ELMo’s hidden representation. Thus, for ELMo,

\[\mathbf{h}_{k,j} = [\stackrel{\rightarrow}{\mathbf{h}}^{LM}_{k,j};\stackrel{\leftarrow}{\mathbf{h}}^{LM}_{k,j}]\]Importantly, ELMo is a character-level language model trained on the 1B Word Benchmark,10 which is shuffled at the sentence level. ELMo outputs 1024-dimensional representations, so the input size to the seq2seq + ELMo model is 1124 (after these representations being concatenated with 100-dimensional GloVe embeddings).

OpenAI GPT

The OpenAI Generatively Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) utilizes a 12-layer Transformer decoder-only architecture,11 a variant of the Transformer,12 for its language model. Since it is decoder-only, it effectively acts as a forward language model; it uses masked self-attention, where every token may only attend to context to its left. The activations for each layer $\mathbf{h}_{:,j}$ are computed as follows:

\[\mathbf{h}_{:,0} = UW_e + W_p\] \[\mathbf{h}_{:,j} = \text{transformer_block}(\mathbf{h}_{:,j-1}) \forall j \in [1,L]\]where $U$ is the input sequence of tokens, $L$ is the number of layers, $W_e$ is the token embedding matrix, and $W_p$ is the position embedding matrix.

OpenAI GPT is trained on the BooksCorpus dataset,13 which, although approximately the same size as the 1B Word Benchmark used by ELMo, crucially contains long stretches of contiguous text (1B Word Benchmark is shuffled at the sentence level). This allows the model to better model long range dependencies. It uses a bytepair encoding (BPE) vocabulary14 with 40,000 merges; the activation corresponding to the last bytepair for each word is used as the corresponding representation for that word in the sequence-to-sequence model. OpenAI GPT generates 768-dimensional encodings, so the input size to the LSTM sequence-to-sequence encoder is 868.

BERT

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) is very similar conceptually to OpenAI GPT. The key difference in architectures is that BERT utilizes a Transformer encoder as opposed to a decoder. Importantly, the Transformer encoder is bidirectional; it is able to condition its representations jointly on both left and right context in all layers. Among the three pre-trained language models used for this paper, BERT is the only one that does this; OpenAI GPT is unidirectional, and ELMo produces independently trained forward and backward representations that it concatenates. This difference can be seen in the image above. Equations 4 and 5 also apply to BERT; the difference is that the self-attention function within each Transformer block is not masked to prevent tokens from attending to subsequent tokens, as in OpenAI GPT. In order to train its bidirectional language model, BERT utilizes a “masked LM,” in which random tokens in the input are replaced with a “[MASK]” token and the model asked to recover the original tokens based on context. BERT is also pre-trained on a second task, next sentence prediction. BERT is trained on BooksCorpus plus English Wikipedia, which provides an additional 2.5M words while maintaining document-level structure and therefore long-range dependency. It uses a WordPiece vocabulary15 of 30,000 tokens. As with OpenAI GPT, the selected encoding for each word is the representation corresponding to the last tokenized piece of that word.

There are two versions of BERT: BERT (Base) and BERT (Large). BERT (Base) was designed to be nearly identical to OpenAI GPT in terms of dimensionality in order to minimally compare the differences in training techniques, directionality, and choice of pre-training corpus. Like OpenAI GPT, it has 12 Transformer layers and generates 768-dimensional encodings that become 868-dimensional inputs to the sequence-to-sequence encoder after concatenation with GloVe embeddings. BERT (Large) is a 24-layer Transformer that produces encodings of dimension 1024 which become inputs of dimension 1124 for the LSTM encoder.

Experiments

Datasets

I used the ATIS, GEO, and JOBS semantic parsing datasets. I used the same versions (with same preprocessing) and splits as in Dong and Lapata (2016).3

Settings

In order to best compare the performance of the various pre-trained representations, all experiments share almost exactly the same settings with the obvious difference of the pre-trained representation used. The specifics of the sequence-to-sequence network used across experiments are reported in the “Methods” section. All models were implemented in PyTorch using the AllenNLP framework. All models were trained on a single NVIDIA V100 GPU using the Adam optimizer16 and a “Noam” learning rate schedule (linear warmup and exponential decay). The learning rates were warmed up for 1000, 800, and 500 iterations on ATIS, GEO, and JOBS, respectively. All experiments utilized a batch size of 16, a learning rate of 0.01, and no regularization in the form of weight decay or dropout (in order to assess the regularization provided by the use of pre-trained representations). Early stopping was performed and based on sequence-level accuracy on the validation set. For ATIS and GEO, models were trained for a maximum of 150 epochs with a patience of 30 epochs; for JOBS, models were trained for a maximum of 200 epochs with a patience of 50 epochs. A beam search of width 5 was used during decoding.

Results

| Model | ATIS | GEO | JOBS |

|---|---|---|---|

| S2S | 79.9 | 68.9 | 71.4 |

| S2S + ELMo | 83.3 | 75.7 | 77.9 |

| S2S + OpenAI GPT | 83.3 | 76.8 | 83.6 |

| S2S + BERT (Base) | 83.5 | 75.7 | 82.9 |

| S2S + BERT (Large) | 83.0 | 73.2 | 80.7 |

The above table shows the performance of each model on the three datasets as measured by sequence-level accuracy.

More detailed results for ATIS:

| Model | Test Acc. | Valid Acc. | Best Epoch | Train Time | Time per Epoch (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2S | 79.9 | 83.3 | 87 | 33:34 | 17.21 |

| S2S + ELMo | 83.3 | 87.0 | 107 | 65:26 | 28.66 |

| S2S + OpenAI GPT | 83.3 | 86.6 | 76 | 66:45 | 37.78 |

| S2S + BERT (Base) | 83.5 | 86.2 | 70 | 42:28 | 25.48 |

| S2S + BERT (Large) | 83.0 | 85.9 | 73 | 65:54 | 38.39 |

More detailed results for GEO:

| Model | Test Acc. | Valid Acc. | Best Epoch | Train Time | Time per Epoch (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2S | 68.9 | 70.6 | 103 | 4:27 | 2.01 |

| S2S + ELMo | 75.7 | 77.3 | 82 | 7:40 | 4.11 |

| S2S + OpenAI GPT | 76.8 | 79.0 | 91 | 9:46 | 4.84 |

| S2S + BERT (Base) | 75.7 | 79.0 | 71 | 6:13 | 3.69 |

| S2S + BERT (Large) | 73.2 | 74.8 | 47 | 8:04 | 6.29 |

More detailed results for JOBS:

| Model | Test Acc. | Valid Acc. | Best Epoch | Train Time | Time per Epoch (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S2S | 71.4 | 71.0 | 147 | 4:05 | 1.24 |

| S2S + ELMo | 77.9 | 83.0 | 80 | 6:29 | 2.99 |

| S2S + OpenAI GPT | 83.6 | 82.0 | 58 | 6:49 | 3.79 |

| S2S + BERT (Base) | 82.9 | 85.0 | 109 | 6:54 | 2.60 |

| S2S + BERT (Large) | 80.7 | 82.0 | 89 | 12:17 | 5.30 |

Including pre-trained features markedly improves performance of the baseline sequence-to-sequence (S2S) model in every case. The differences in absolute accuracy between the baseline and the next-worse model are 3.1%, 4.3%, and 6.5% on ATIS, GEO, and JOBS, respectively, while the differences between the baseline and the best-performing model are 3.6%, 7.9%, and 12.2%, respectively. As the size of the dataset shrinks, the difference in performance over the baseline grows, as well as the difference in performance between the best- and worst-performing pre-trained models. This supports the trend commonly reported in the literature: pre-training is most important to good performance on smaller datasets. These results show that incorporating features that have been pre-trained as a language model into a sequence-to-sequence model is a simple way to significantly increase performance; the baseline models were tuned on the validation set to optimize performance, but the models with pre-trained features used exactly the same architecture and training settings with the addition of pre-trained features, no further tuning, and noticeably improved performance across the board.

It is less clear which of the four pre-trained models is the best. Surprisingly, it is not BERT (Large), which performs even worse than ELMo on ATIS and GEO, in addition to being the slowest model computationally in terms of time per epoch. This could not be a matter of its use of a Transformer encoder or the dataset on which it was trained, as these are shared by BERT (Base), which outperforms it on every dataset; therefore, it seems likely that it is instead its extra capacity causing it to overfit. Regularizing each model to optimize performance by including weight decay or dropout might result in BERT (Large) outperforming all the others, but on its own, it has less of a regularizing effect than the others.

The most likely candidates for the best pre-trained model are BERT (Base) and OpenAI GPT. Interestingly, OpenAI GPT was the best model on GEO and JOBS, despite being unidirectional, having a nearly identical capacity as BERT, and being trained on only a portion of the data on which BERT was trained. Perhaps this makes the model less inclined than BERT to overfit on smaller datasets such as GEO and JOBS. Another possibility is the difference in the tokenization schemes between the two: BERT uses a WordPiece vocabulary, while OpenAI GPT uses a BPE vocabulary. Although seemingly insignificant, this difference could nonetheless affect the comparative performance of the models, especially since the versions of the datasets are the same as those used by Dong and Lapata (2016), who, in addition to anonymizing variables, also changed the spelling of some terms in the English questions, most likely to standardize the tokens (eliminate plurality, variations, etc.) in order to have a smaller vocabularly for their models. For example, one question in the ATIS training set reads “which airlin provid busi class flight” and one from GEO reads “what is the capit of the state with the highest elev.”

Although WordPiece and BPE vocabularies are designed to alleviate the problem of out-of-vocabulary words, the small differences between them might account for part of the reason why OpenAI GPT performed better than expected in comparison to BERT (Base). This idea is further supported by the surprising performance of ELMo. Although ELMo uses LSTMs instead of Transformers and has been outperformed by both OpenAI GPT and BERT in published results on language understanding tasks, it ties OpenAI GPT in performance on ATIS and BERT (Base) on GEO. It seems likely that a major reason for this surprisingly good performance is that at its core is a character-level language model, which should help it adapt to incorrect English and out-of-vocabulary words like the examples shown above.

Another possible explanation for ELMo’s unexpectedly good comparative performance is that one of the best advantages of the Transformer-based models is ineffective here: their ability to model long-range dependencies better than ELMo. OpenAI GPT and BERT were trained on contiguous stretches of text of up to 512 tokens in order to do well on complex tasks with large inputs, whereas ELMo was trained on a corpus shuffled at sentence level in addition to being a character language model, both of which should hamper its ability to model dependencies over long sequences of words. Fortunately for ELMo (and perhaps unfortunately for OpenAI GPT and BERT), modeling long-range dependencies does not seem to be important to semantic parsing; even the longest English questions in these datasets are no more than 50 words or so in length.

Nonetheless, BERT (Base) and OpenAI GPT display the strongest performance here. Another consideration between the two is the difference in their speed; despite both being 12-layer Transformers, OpenAI GPT was computationally slower than even ELMo, while BERT (Base) was the second-fastest model behind the baseline (as measured in time per epoch). Despite their differences, they perform extremely similarly across the three datasets, likely as a result of their nearly identical architectures. Further research is required to more precisely determine how their differences affect downstream performance in various settings, but most importantly, these models greatly improve the performance of the baseline sequence-to-sequence models without further tuning.

Conclusion

As far as I am aware, this paper represents the first attempt to extend these recent methods to the realm of language generation; they were all designed to work with and tested on language understanding tasks. A comparison of the results suggest that OpenAI GPT and BERT (Base) offer the easiest, most immediate, and largest improvement in performance over the sequence-to-sequence baseline, balancing power with capacity. It is important to point out that the experiments here were designed with maximum comparability in mind. Further research is required to determine the effect of various regularization strategies, increasing the capacity of the sequence-to-sequence model, fine-tuning the entire models instead of learning how to best utilize existing features, etc. Nonetheless, these results reaffirm the power of the unsupervised pre-training techniques that have recently become so popular in the field.

Minh-Thang Luong, Hieu Pham, and Christopher D. Manning. 2015. Effective approaches to attention-based neural machine translation. CoRR abs/1508.04025. http://arxiv.org/abs/1508.04025. ↩

Robin Jia and Percy Liang. 2016. Data recombination for neural semantic parsing. CoRR abs/1606.03622. http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.03622. ↩

Li Dong and Mirella Lapata. 2016. Language to logical form with neural attention. CoRR abs/1601.01280. http://arxiv.org/abs/1601.01280. ↩ ↩2

Jeffrey Pennington, Richard Socher, and Christopher D. Manning. 2014. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In In EMNLP. ↩

Matthew E. Peters, Mark Neumann, Mohit Iyyer, Matt Gardner, Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2018. Deep contextualized word representations. CoRR abs/1802.05365. http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.05365. ↩

Jeremy Howard and Sebastian Ruder. 2018. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. CoRR abs/1801.06146. http://arxiv.org/abs/1801.06146. ↩

Alec Radford. 2018. Improving language understand- ing by generative pre-training. ↩

Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2018. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. CoRR abs/1810.04805. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805. ↩

Prajit Ramachandran, Peter J. Liu, and Quoc V. Le. 2016. Unsupervised pretraining for sequence to sequence learning. CoRR abs/1611.02683. http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.02683. ↩

Ciprian Chelba, Tomas Mikolov, Mike Schuster, Qi Ge, Thorsten Brants, and Phillipp Koehn. 2013. One billion word benchmark for measuring progress in statistical language modeling. CoRR abs/1312.3005. http://arxiv.org/abs/1312.3005. ↩

Peter J. Liu, Mohammad Saleh, Etienne Pot, Ben Goodrich, Ryan Sepassi, Lukasz Kaiser, and Noam Shazeer. 2018. Generating wikipedia by summarizing long sequences. CoRR abs/1801.10198. http://arxiv.org/abs/1801.10198. ↩

Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention is all you need. CoRR abs/1706.03762. http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762. ↩

Yukun Zhu, Ryan Kiros, Richard S. Zemel, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Raquel Urtasun, Antonio Torralba, and Sanja Fidler. 2015. Aligning books and movies: Towards story-like visual explanations by watching movies and reading books. CoRR abs/1506.06724. http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.06724. ↩

Rico Sennrich, Barry Haddow, and Alexandra Birch. 2015. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. CoRR abs/1508.07909. http://arxiv.org/abs/1508.07909. ↩

Yonghui Wu, Mike Schuster, Zhifeng Chen, Quoc V. Le, Mohammad Norouzi, Wolfgang Macherey, Maxim Krikun, Yuan Cao, Qin Gao, Klaus Macherey, Jeff Klingner, Apurva Shah, Melvin Johnson, Xiaobing Liu, Lukasz Kaiser, Stephan Gouws, Yoshikiyo Kato, Taku Kudo, Hideto Kazawa, Keith Stevens, George Kurian, Nishant Patil, Wei Wang, Cliff Young, Jason Smith, Jason Riesa, Alex Rudnick, Oriol Vinyals, Greg Corrado, Macduff Hughes, and Jeffrey Dean. 2016. Google’s neural machine translation system: Bridging the gap between human and machine translation. CoRR abs/1609.08144. http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.08144. ↩

Diederik P. Kingma and Jimmy Ba. 2014. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. CoRR abs/1412.6980. http://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980. ↩